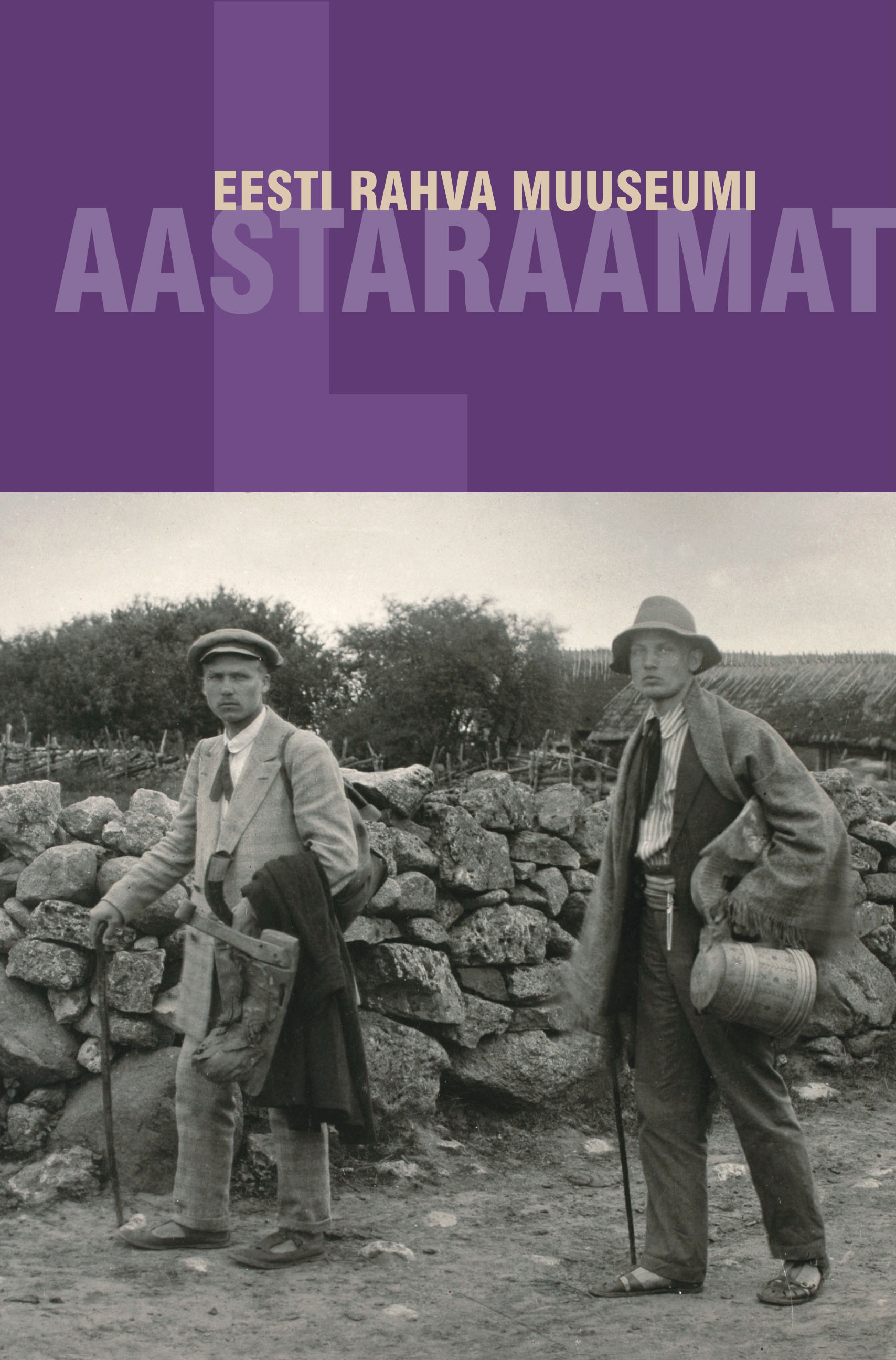

Gustav Ränk 1928. aasta suvel Karjalas

Artikli avamiseks täies mahus vajuta paremas veerus asuvale nupule PDF.

Abstract

Gustav Ränk in Karelia in the summer of 1928: analysis of ethnographical fieldwork

Густав Рянк в Карелии летом 1928 года

By 1928 Gustav Ränk (1902–1998), later on a renowned ethnologist and the first Estonian professor of ethnology, had studied ethnography at Tartu University for three years and worked at the Estonian National Museum for two years. The expedition to Finnish Karelia was his first research trip outside Estonia. It lasted for more than a month, and during this time Ränk visited Sortavala, Suojärvi, Korpiselkä, Suistamo and Salmi parishes. The main objective of the expedition was to supplement the Finno-Ugric collections of the museum. The department of kindred peoples was currently being established at the ENM and artefacts from other Finno-Ugric peoples were intended to be exhibited to visitors, but they were rather scarce at the museum.

While travelling in Karelia, Gustav Ränk made notes about the collected artefacts in the collection book and also kept a fieldwork diary, which includes colourful descriptions of the surrounding life and fieldwork processes as well as the author’s evaluations and feelings. Ränk describes the Karelians as friendly, kind, helpful and religious people, who lead a quiet life in their (usually) tidy homes, often drink coffee and earn a living with lumbering in winter as well as tilling their small plots. By analogies he compares the Karelians, Setus, Finns and Estonians with each other. For the Lutheran Finland and Estonia the first two are as Orthodox hinterland inhabitants, actually compatriots, who are considered as “small brothers”. When reading the diary, it seems that before going to fieldwork in Karelia, Ränk depreciated the Setus and regarded Karelia as similar to Setumaa. However, seeing the Karelians being better off, he had to revise his viewpoints. He glorified the Finns, being proud of their common origin with Estonians. So he created kind of hierarchy of nations, where the Setus occupied the lowest position, being preceded by the Karelians and Estonians, with Finns at the top.

At fieldwork in Karelia Ränk collected more than a hundred artefacts, which were related to different spheres of Karelians’ everyday life. When performing his main task, he was quite selective, yet, this way proceeding from the then collection principles at the ENM. The museologists of the 1920s were, above all, interested in the old peasant culture undamaged by modernization, and they tried to find archaic and beautiful artefacts characterizing it. The last criterion applied, first and foremost, to folk costumes. In Ränk’s diary the problem of finding folk costumes emerges; i.e., according to the collector’s value judgments they were not available. The value or worthlessness of the artefacts collected from other spheres of life is not discussed in his diary. The majority of the artefacts collected by Gustav Ränk were exhibited already at the end of 1928, when the Finno-Ugric department was opened at the ENM.

From among everyday problems in fieldwork the fact that Ränk could not speak the local language emerged first. This was a serious obstacle for the first couple of weeks; later on he did not mention language deficiency any more. Ränk was not especially worried about accommodation and food – he staked on the hospitality of local people and did not have to be disappointed. He also used the services of Karelian inns. Being at fieldwork did not mean only constant work for Ränk. Local people willingly introduced him to their way of life, he went to a Karelian village hop and also met a female Finnish student, with whom he twice spent time longer. He had a crush on her; however, he is not known to have met her later on again.

Undoubtedly, the expedition to Karelia in the summer of 1928 was an interesting experience for Gustav Ränk. A young student, who had formerly been at fieldwork in Saaremaa, Hiiumaa and Setumaa as well as at Lake Võrtsjärv, was now away from native Estonia, in a completely unfamiliar environment. This is probably why he wrote such an interesting diary (he simply had so many impressions), which totally differs from his other ones written in Estonia in the 1920s (comprise only short notes). Also expedition to Karelia was meant purely for collecting artefacts, and therefore Ränk had no obligation to obtain scientific material, for instance, for the Ethnographical Archive or his own research, which was of primary importance in case of his fieldwork done in Estonia.

Резюме Марлеэн Ныммела

Густав Рянк (1902–1998), в будущем известный этнолог и первый эстонский профессор этнологии, к 1928 году успел проштудировать три года этнографию в Тартуском университете и проработать два года в Эстонском национальном музее. Экспедиция в финскую Карелию была его первой исследовательской полевой работой за пределами Эстонии. Экспедиция, в течение которой Рянк побывал в приходах Сортавала, Суоярви, Корписелькя, Суйстамо и Сальми, продолжалась более месяца. Целью поездки было укомплектование финно-угорской коллекции Эстонского национального музея. В ЭНМ как раз создавался отдел родственных народов, и для посетителей хотели экспонировать предметы других финно-угорских народов, которых в музее было еще мало.

Будучи в Карелии, Густав Рянк вел тетрадь описи собираемых предметов и дневник полевой работы, содержащий яркие описания окружающей жизни и процессов полевой работы, а также личную оценку происходящего и путевые впечатления. Рянк пишет о карелах как о дружелюбных, добрых и верующих людях, которые спокойно живут в своих (обычно) чистых домах, часто пьют кофе и зарабатывают на жизнь зимней заготовкой леса и обработкой своего небольшого участка земли. Основываясь на аналогиях, он сравнивает между собой карел, сету, финнов и эстонцев. Первые два народа для лютеранских Финляндии и Эстонии являлись жителями православных провинций, соотечественниками, к которым относились как к «младшему брату». Читая дневники, чувствуется, что Рянк недооценивал народ сету и, отправляясь в экспедицию, представлял себе, что Карелия похожа на Сетумаа. Однако, увидев лучшие условия жизни карел, он был вынужден пересмотреть свое мнение. Финнов он оценивает высоко, одновременно чувствуя гордость за родство эстонцев с ними. Так, возникает определенная иерархия, на нижней ступени которой стоят сету, затем карелы и эстонцы, и на верхнем месте располагаются финны.

В карельской экспедиции Рянк приобрел более 100 предметов, отражающих разные стороны жизни карел. Выполняя свою основную задачу, он был весьма придирчив в выборе экспонатов, исходя из тогдашних положений собирательской работы Эстонского национального музея. В 1920-х годах музейщики были заинтересованы в предметах крестьянской культуры, не затронутых процессами модернизации, старались найти архаические и аттрактивные предметы. Последний критерий относился, прежде всего, к народной одежде. Так, в дневнике Рянка на первый план выставляется проблема поиска предметов одежды, по мнению собирателя, достойных предметов практически невозможно найти. О других же предметах, об их достоинстве или значимости, автор в дневнике заметок не оставляет. Большая часть предметов, собранных Рянком, была экспонирована уже в конце 1928 года, когда был открыт финно-угорский отдел экспозиции Эстонского национального музея.

Одной из каждодневных проблем, с которой Рянк столкнулся в экспедиции, стала проблема языка, ибо он не владел местным языком. Незнание языка особо мешало ему в первые две недели, в дальнейшем в дневнике он об этом уже не отмечает. О ночлеге и еде Рянк не волновался, надеясь на гостеприимство местных жителей, в чем ему и не пришлось разочароваться. Он пользовался также услугами постоялых домов. Нахождение в экспедиции не означало для Рянка только работу. Местные с удовольствием знакомили ему свою жизнь, Рянк посещал карельские деревенские праздники, завел знакомство со студенткой-финкой, в обществе которой дважды провел свое время.

Карельская летняя экспедиция 1928 года, несомненно, стала для Густава Рянка интересным жизненным опытом. Молодой студент, ранее побывавший в полевых исследованиях на эстонских островах Сааремаа и Хийумаа, а также на Сетумаа (территория проживания сету, юго-восточная Эстония, побережье Псковского озера) и у озера Вырцярв, находился вдали от родины, в совершенно чужом окружении. Вероятно, именно этим можно объяснить занимательность данного дневника (просто впечатлений было очень много), который совершенно отличающается от других дневников, написанных им в 1920-х годах во время эстонских экспедиций (содержащих лишь краткие записи). Одновременно, поездка в Карелию была связана, прежде всего, со сбором предметов, и у Рянка не было обязанностей собирать научный материал, например, для этнографического архива музея или тематического исследования, что было важнее во время его полевых работ в Эстонии.